Ann Cook recorded two blues songs in New Orleans on March 7, 1927, which were released on Victor Talking Machine Co. 78 rpm record #20579. More than twenty-two years later, on July 21, 1949, also in New Orleans, she recorded a gospel song, released on one side of the American Music 78 #536. These records and a few pictures are the sole testaments of, the relics and the remnants of her life. Many have left less to be remembered by, especially those who lived like she did as a Black person in the times she did. Perhaps if she knew that some people, even if only a few who were living lives unimaginably different from hers, still listened to her songs, she would be perplexed but proud.

What little we know about her is gossip, hearsay, and public records, which, while maybe factual, are only that. There are facts and then there are stories, some of which are true, truer than facts. Ann Cook only had nine minutes, three 78 rpm record sides, to tell her story. There is much untold. You can listen to her songs and make up your own story.

Blues Who's Who and some online sources claim incorrectly that Ann Cook was born May 10, 1903 in St. Francisville, W. Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, a town about thirty miles north of Baton Rouge. Actually, she was born in 1886, probably in April, in the village of Fazendeville, St Bernard Parish, approximately eight miles from New Orleans, as the third eldest of the seven children of Carl Cook, born in 1849 and his wife Rose, born in 1852. Fazendeville was a small African-American community founded by formerly enslaved people after the Civil War, which flourished and grew, founded its own Baptist Church, and became known for its brass band concerts. Carl Cook gave one of the speeches on New Year's Day, 1890, at a village commemoration of the Emancipation Proclamation's issuance.

The next fact we know about Ann Cook is that on October 22, 1903, she married a man named William Johnson in St. Bernard Parish, probably at the Fazendeville Baptist Church. Nothing is known about him, and apparently, he and Cook split sometime during the next few years, and for the rest of her life, she called herself "Ann Cook."

In 1908, Ann Cook was in New Orleans, no longer in rural Fazendeville, where she probably worked in the fields, or maybe there was no work for her there and she came to the city to find a job. Or maybe life in a small town bored her, where the church was the center of social life, everyone knew everyone else, and there were no clubs, bars, or theatres. Maybe she liked to drink and dance, was wild, and the "respectable" jobs; maid, cook, laundress, available to Black women didn't appeal to her.

We do know that on December 12, 1908, she was arrested for prostitution and the theft of $5, at the corner of Rampart and Julia Streets in Storyville, the legally designated district in which the police turned a blind eye to prostitution and almost all non-violent crime. She was in front of the Red Onion, a legendarily tough saloon and dance hall, later to be immortalized in the titles of several early jazz tunes and about seven blocks, but an immeasurable social distance, from, on the other, the east side, of Canal St. in "whites only" Storyville, Lulu White's, Willie Piazza's and the expensive pleasure mansion houses with imported furniture, piano playing "professors" and octoroon women. To be arrested for prostitution in Black Storyville, Cook must have broken one of the unwritten rules for the comportment of women working on the streets. She told the police her occupation was "cane cutter." Maybe she was new in town and to the life and wasn't sure what she was yet.

For decades to come, Cook would work and live in the fifty block area of Black Storyville, also called "Back O' Town," or just "The Battlefield," and become well known, both as a singer and a tough woman of the streets. At some point, probably in the 'teens, Cook became a fixture singing at Joe Sogretto's honky-tonk at the corner of Saratoga and Perdido. But when she wasn't singing or maybe even when she was, she still worked on the streets.

On October 21, 1913, she was arrested at the corner of Poydras and Saratoga, a block west of Sogretto's tonk, for disturbing the peace and was sentenced to fifteen to twenty days in jail. On August 8, 1915, she was arrested a block north of Sogretto's at the corner of Perdido and S. Franklin Streets for disturbing the peace and fighting with two other women. The occupation of all three was listed on the arrest docket as "prostitute."

On November 12, 1917, under pressure from the U.S. Navy, which had a large training facility in New Orleans, Storyville was officially closed. On the east side of Canal Street, jazz bands played while the madams and their servants and pets moved out and the mansions were abandoned. Churches vowed to help the women who worked in the district onto the path of righteousness, but in Black Storyville, life and the life went on as before.

Ann Cook's life did, too, but unknown to us until Christmas Day, 1922 when she surrendered herself at a police station and was arrested for the murder of Lethia Robertson on Christmas Eve. Robertson was a twenty-four-year-old Black woman who had been arrested numerous times for street offenses, including "practicing prostitution," and was reputedly a member of a gang of "well known thieves."

When she was killed, she was living on South Rampart St, right around the corner from 1123 Poydras where Cook lived. The women likely knew each other because, during the prior July, Robertson and two other women had been arrested for "accosting passersby" in front of 1123 Poydras. What happened on Christmas Eve is unknown, possibly holiday celebration became excessive, and a territorial dispute brewing between the women developed into a brawl. Whatever the circumstances that led to Robertson's death, Cook must have made a reasonably credible claim of self defense, because she was not convicted of murder or probably even tried. The death of a Black woman working on the streets in "The Battlefield" was given little attention by the police. On the arrest docket under "Offense" is written "Murder of Lethia Robertson-Col” (ie Colored).

We know Cook was on the streets in Back O' Town on February 26, 1924, when she was arrested at the corner of Poydras and Saratoga for disturbing the peace and using obscene language. Probably, now, after her involvement in Robertson's death, she had acquired her nickname, "Bad Ann" and become a target of police harassment.

Reportedly, during this period, she was singing at the Red Onion and the Calliope St. Café. Musicians admired her talent. Clarence Williams wrote of her, "She would sing according to the temperament and moods of the customers and could sing endless verses to one song." Another musician, Earl Humphrey, said, "She was just one of them real outstanding barrelhouse blues singers." Rosalind Johnson said, “The first record Ann Cook made stopped the traffic on Rampart Street. She was a great entertainer.”

Her life on the streets continued. On August 18, 1926, she was arrested for prostitution with "no visible means of support" with two other women at 941 Julia St. a few blocks south of the Red Onion.

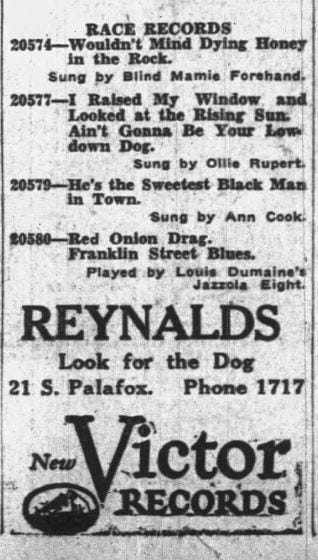

The Victor Talking Machine Company, after stops in Memphis and Atlanta, came to New Orleans in the first week of March 1927 and set up a temporary recording studio, probably in a hotel. On March 7, they recorded three tunes by Louis Dumaine's Jazzola Eight. One of the tunes Dumaine's band recorded was entitled "Red Onion Drag," a tribute to the honky tonk where they probably had an ongoing gig. Undoubtedly, they knew Cook and had accompanied her singing there. One or more of the band members said later that they recommended her to Victor, searched for her, found her, and then brought her to the studio after she had been drinking all night.

Cook, accompanied by Dumaine's cornet and three members of his group, Willie Joseph's clarinet, Morris Rouse's piano, and Leonard Mitchell's banjo recorded two songs; "Mama Cookie" and "He's The Sweetest Black Man In Town." Both are southern, rural blues, sounding nothing like the "Vaudeville Blues" recorded in the north by dozens of popular female singers and by other New Orleans singers like Lizzie Miles and Genevieve Davis. Cook's voice and style are raw and harsh, similar to that of Ma Rainey, who performed in New Orleans and wintered there. It is likely that Cook knew, was friendly with Rainey, and was influenced by her singing.

"Mama Cookie" begins with Cook's swaggering announcement, "Hey, it's Mama Cookie's blues" and then she sings, proclaiming proudly, "Barrelhousin' now, been barrelhousin' all my days." Cook sings four more traditional blues verses while the band, clearly familiar with her phrasing and time feel, plays a stomping two beat, Black Bottom dance rhythm, the horns improvising freely behind her. It's lowdown, funky, "2 am in the Red Onion and everybody's drunk" music.

At least two takes of "Mama Cookie" were recorded and have been released. The band arrangement is the same, but Cook, in typical, early rural blues fashion, improvises her lyrics. The first two verses are the same in both versions, but after them, she changes the order of verses and sings different ones each time. "Mama Cookie" was not really a "song" but just Cook singing the blues, and in the Red Onion, she would probably sing, without repeating a verse, for ten minutes, a half hour or more, so long as people were dancing.

"He's The Sweetest Black Man In Town," credited as another Cook original, is a twelve bar form without the usual blues chord changes, except for the fifth chorus where the band from force of habit slips back into I-IV-V for a few bars. Part of the melody is reminiscent of Sam Morgan's "Everybody's Talking About Sammy," and both songs were probably based on the same New Orleans folk tune. Cook's belting, raspy, chest voice delivery shows that she has spent time testifying in church, yet she still brings plenty of raunch and sex to what is a fairly trite lyric. Once again, the band lays down a solid, grooving dance beat with the little known Willie Joseph playing some superb wailing, deeply bluesy, Johnny Dodds-like clarinet behind Cook.

Victor recorded a glee club, some gospel, some pop, and some jazz during the next few days and then left New Orleans. The two songs Cook recorded are classics: gutbucket, saloon blues accompanied by a superb New Orleans jazz band. Recording sessions at that time were typically four songs per artist. Undoubtedly, Cook, a veteran of the honky-tonks, knew many more tunes, and it's unfortunate that Victor didn't record her singing some of them. Perhaps the story the musicians told is true, and she did arrive at the session already drunk, and after drinking some of the whiskey provided at record sessions to "loosen up" the artists, became so impaired that the recording director terminated the session.

Cook was paid $100 (about $1800 in 2025) for the two songs, which was the standard payment for an unknown artist, and they were released on Victor 78 rpm record #20579, probably in the spring of 1927. Cook said later the record was so popular that the police had to be called to the music stores to control the crowds of eager buyers. This is an implausible claim, but the record likely sold well in New Orleans and undoubtedly increased Cook's local celebrity and popularity. There were five recording trips to New Orleans by various record companies in 1928 and 1929, but Ann Cook was not recorded again. Did she refuse offers? Had she developed a reputation for unreliability or being difficult?

Nothing is known about Ann Cook's life for nearly the next five years. Maybe her life in "The Battlefield" continued on as before because it was the life she knew and, she thought, better than any other life she could have. Or maybe the Victor record boosted her singer career to full time and she found herself in a happy love/domestic relationship. Maybe her life became different and better, and she wanted it to stay that way, but it was not to be for sad, though inevitable reasons, and then there was heartbreak and despair.

We only know facts, and Cook seems to have fallen in a plummeting crash like all of Depression America, sea to sea, to rock bottom in 1932. On February 27, she was arrested at 720 Dryades St., her residence, for prostitution, pending investigation of a murder. The facts are unknown, but Cook was probably only tangentially involved or a witness as she was paroled a few hours later.

On October 8, she was arrested for prostitution again at 720 Dryades with two other women. On October 15, again at 720 Dryades, she was arrested for fighting with another woman and for disturbing the peace. Finally, on December 15, she was arrested for being "a well known prostitute with no visible means of support." This time, she was not paroled, and it seems likely that she was sentenced to the standard 30 day term for prostitution or, given her record, considerably more.

Now we come to the great mystery of Ann Cook's life- why, how, and when she became a different person, a new, born again, devout Christian person. All is speculation. Maybe one day in Storyville, she wondered how she had come to this place and this life, and the weight of the memories of the years was borne down upon her and began to press ever more heavily upon her without respite. In the early morning hours when she couldn't sleep, she was, in her memories, now a terrible stranger, a person she must flee from, a person who had never given her peace and never would. There were wandering preachers on the streets, churches in Storyville, and mass baptisms in the Mississippi. When, in her white robe, she walked into the river and the minister and Jesus took a hold of her and she let herself fall back beneath the water, she was pulled from it a new pure woman loved by the whole church and Jesus.

When Bill Russell (1905-1992), a white man born in Canton Missouri, came to New Orleans in 1943 to record traditional jazz, he had lived a very different life than Ann Cook or anyone else living or working in "The Battlefield." He had begun playing violin at age ten, studied music in Chicago in the early '20s, and studied violin privately in New York in 1927 before studying composition at the Columbia University Teacher's College. He embarked on a career as an avant- garde classical composer and had one of his pieces played at Carnegie Hall in 1933. When performing and touring as a member of The Gate Shadow Players, a Chinese music group, he became interested in jazz and began collecting records and writing for jazz magazines.

Russell soon became convinced that jazz had originated in New Orleans and become diluted and popularized when it left the city in the exodus of musicians to the north in the teens and twenties and that the music still being played by older musicians who had remained behind in New Orleans was the pure jazz, a form of folk music—music for the folks—which should be preserved. He devoted the rest of his life to recording New Orleans Jazz and documenting its history.

In May 1943, Russell came to New Orleans to record traditional jazz without commercial considerations for records, which would eventually be released on the Climax label, a subsidiary of Blue Note Records. He had heard Ann Cook's Victor record, and though she had been off the music scene for about ten years, she was one of the singers and musicians he wanted to record, and he asked clarinetist George Lewis to find her. He did, and according to Russell:

She wanted too much money. She kept saying that Victor had paid her $100 to make two sides in 1929 (sic). I told her I couldn't pay her that....I think I offered her about $30, but on principle I couldn't offer her any more than that for two numbers, when all the other guys had worked all afternoon (for $20).

Cook, never appeared at the session.

In July 1944, Russell was back in New Orleans, now making recordings for his own American Music label. Once again, he contacted Cook.

When I went with George (Lewis), she was living in a two-room mobile home—although it had no wheels. It was pretty run down, in the 'battlefield' area uptown from South Rampart. Although she was now in the church, George was a little afraid of her as she had a bad reputation from the old days….(He) and (banjo player, Johnny) St. Cyr were afraid of her as she had killed a number of people in her younger days. George said, ‘Sometimes she'd shoot 'em, sometimes she'd cut 'em to death.’… She always had some envelopes for her church contributions, and it was difficult to leave without giving her some change.

Russell offered her $35 for two songs. Cook, once again, insisted on $100 and refused to record for less.

Russell, more determined to record Ann Cook than ever, was back in New Orleans again in July 1949. He tracked her down at 2227 Thalia St., where she had moved from the trailer. She told him again that Victor had paid $100 and she didn't come to the sessions in in 1943 and 1944 because he hadn't offered "any money."

I told her I was hardly in a class with Victor and I could only pay her $50 for two sides. I also asked her about the blues again, but she said at once, ‘No, I belong to the church now, I don't sing no blues.’

He gave her the address for the session and taxi money but, "I still wasn't convinced she'd ever show up.

With admirable persistence, he went back to see her the next day.

She started out by saying she had talked to her manager and he said $50 wasn't enough. He thought she should have $65. I told her I didn't think she needed to give him a cut or involve him, since I had gone direct to her. She seemed to back down on the manager talk and said he wouldn't get any commission. But before I left, she asked again for $65. I offered her $55 to show that I'd pay as much as possible but that was all I could manage. I acted like I didn't expect her to come, but she said, ‘Oh, I'll be there alright.’ She then sang the two songs she had selected. I'd already given her enough for the taxi, but gave her a little more and told her to be there by 7pm.

Still having little faith that Cook would appear, Russell contacted another singer as a backup, but:

Promptly at 7 o'clock, a taxi drove up and out stepped Ann Cook. She was really all dressed up-- a big flowered print dress and a large fluffy broad-brimmed hat decorated with flowers. She entered looking like she owned the whole town, although I later found out that she's borrowed some of the clothes from a neighbor. As I began to take some photos of her, she noticed some artificial flowers in a vase on the piano, so I took one of her holding the bouquet. Unfortunately, she was wearing her glasses and when I had the film developed, the flash had reflected in her glasses and ruined the photo.

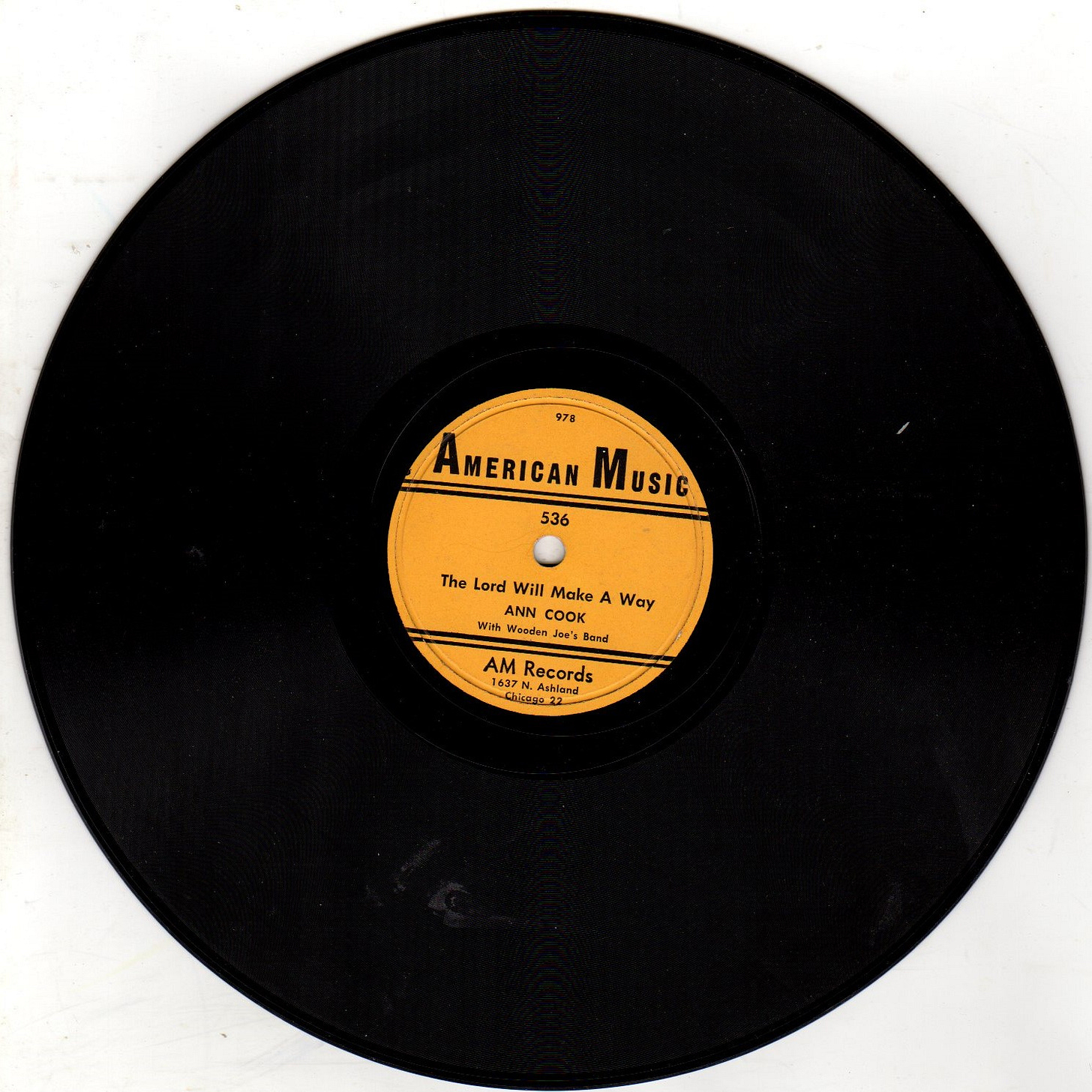

Cook and the band began trying to record her first song, "Where He Leads Me, I Will Follow" but her tempo was unsteady, and she sometimes dropped beats confusing the band. After four bad takes, Russell gave up and suggested they try her other song.

‘The Lord Will Make A Way’ seemed to go better but the first try was still unsatisfactory. It was now 8:30 and Ann Cook was getting restless. She told everybody how the Victor date with Louis Dumaine had (not) taken ‘so many minutes.’ She seemed to think that every take she had done had been OK. She finally agreed to try the song once more, but remarked ‘I'm tired’ and that she wanted to go. She then surprised everyone by starting the second take in a different key. ... When we played it back, she said, ‘That's good enough’ and no matter how I begged her, she refused to sing it again. I paid her $55 and gave her the taxi fare home.

The second and final take of "The Lord Will Make A Way" issued on American Music 78 #536 is a shambles. The band plays tentatively, trying to follow Cook's erratic phrasing while attempting to find the key she is singing in, and trumpeter Wooden Joe Nicholas never succeeds. She had been singing in a church choir for years, not jazz with a band and is clearly out of practice. Her voice is still powerful, raw, and exciting but her gospel style lacks the conversational intimacy of the Victor recordings when she sang blues. Russell must have been terribly disappointed with the result of six years of determined effort to record Ann Cook.

But still, he wanted a better picture of Cook, and:

..A few days later (Monday July 25) I went up to her house to take some more photos of her without her glasses. She sent a little girl over to her mother to ask if she could borrow a dress, and got all dressed up. I took some photos of her in her yard. She said she wanted her name on the records as ‘Ann Cook of the Greatest St. Matthew #2 Baptist Church’ and got me to write it down.

So, Russell took his pictures of Ann Cook with flowers in her hair in a flowered dress, borrowed, like the one she wore at the recording session a few days before, and again, like she had then, looked straight at the camera without pretense or endearment, only a hard won sense of self. "I may be a poor woman in a borrowed dress who the devil and the blues got ahold of and I been 'buked and scorned but I came through it all and I am a new woman, proud and beautiful and saved." Then Bill Russell went on his way and Ann Cook returned the dress.

Nothing more is none of the life of Ann Cook until her death on September 29, 1962, of a heart attack at home. She is buried at the Ellen Cemetery in St. Bernard, Louisiana.

Thanks to Richard Bowman of the Golden Mystics Of Old Time Music for advice and photos